Remembering the deceased has been at the core of many human rituals and celebrations. This especially rings true in Mexico, where family and friends gather once a year to pray and tell anecdotes about the departed, build altars to encourage their souls to visit the human realm, and even dress up as the dead to materialize their return.

Featuring colorful calaveras — skulls that inspire anything from food to costumes — food-filled altars, and bright, fragrant marigolds; the celebration of Día de los Muertos has become an essential component of Mexico’s national identity.

While the iconic celebration has long been portrayed as a revival of indigenours pre-Hispanic culture — and taught as such in the nation’s school system — historical data suggests that the way this holiday is celebrated today is the result of the country’s political and ideological climate in the 1930s, while the spiritual essence of the celebration has largely been lost.

Indigenous cosmological views

Honoring the deceased and helping their souls reach paradise in the afterlife was a primary spiritual aspect of the indigenous groups that once inhabited Mesoamerica — the area comprising southern North America and most of Central America.

It was customary for the people of Teotihuacan, in today’s Valley of Mexico, to perform painstaking rituals to guide the departed soul to one of the four paradises — that of children, adolescents, adults or elders — depending on the age at which the person passed away.

The Maya and the Aztecs had similar views and believed that the fate of the departed souls depended on the type of death they had suffered. Thus, according to Aztec spirituality, those whose death was related to water, those who had died in war, those who had a natural death, and children who had died in childbirth or before their naming ceremony, all belonged to different paradises.

A common theme among pre-Hispanic cultures, and probably the precursor of today’s ofrendas — home altars in honor of the dead — was the offering of two types of objects: those that had been used by the deceased and those that would be needed during their journey beyond the grave.

That is why Teotihuacan rituals were usually accompanied by food, copal, vessels, knives, jade stones and seeds; and the reason why Mexicans today furnish their altars with the favorite foods and drinks of the departed, as well as with their favorite objects or articles during their earthly life.

In addition to commemorating the passage of souls to the afterlife, these rituals also celebrated and recognized the life and legacy of the recently deceased. The Nahua, in particular, used altars to pay homage to those who had lost their lives during noble undertakings, mainly warriors and women who died in childbirth.

The soul and the afterlife in light of Catholic belief

When the Spaniards arrived in America in the 15th century, they brought and established Christian traditions. Two solemnities were especially important: All Saint’s Day and All Souls’ Day, which were celebrated on November 1st and 2nd, respectively.

The two celebrations were part of a Christian season known as “Allhallowtide,” which was a time to remember the dead; including martyrs, saints and all faithful departed. The period began on the eve of All Saint’s Day — October 31st — when people would hold a vigil as preparation to honor all saints and pray for recently departed souls.

Far from lamenting the death and suffering of the faithful, All Saints’ Day celebrates the ascension of souls who, having overcome purgatory, have been totally sanctified and enjoy eternal life in the presence of God. It commemorates the spiritual efforts of those who, after enduring the immense suffering of purging their sins and purifying themselves, have finally reached Heaven.

The liturgical color of this celebration is white, symbolizing the victory and life of the souls that constitute what is known as the Church Triumphant. It is, in essence, a universal celebration of spirituality and a reminder of the importance of having spiritual aspirations.

But what about the souls that have yet to reach Heaven? The following day, November 2nd, is dedicated to those who may be suffering in purgatory. Known as All Souls’s Day or the Commemoration of All Faithful Departed, this observance is an opportunity to remember deceased friends and relatives, and to elevate heartfelt prayers for the ascension of their souls.

In contrast to the joyous celebration of the first day, All Souls’ Day is an occasion for sacrifice and prayer. On this day, many Christinas hold masses and visit the cemeteries where their loved ones were buried to place flowers and candles in their memory. Since prayers for the dead are at the core of this tradition, November 2 is also called the Day of the Dead among Christians and Catholics.

The way in which Indigenous and Spaniards perceived the afterlife and the need for souls to reach a glorious destination soon proved to have similarities. As both cultures had their sights set on the celebration of earthly life and the elevation of the spirit, the tradition of remembering and honoring the departed remained a spiritual tradition for years.

The veneration of death: an alti-clerical move

The distinction between venerating the dead and venerating death has become key to understanding the origin of today’s Day of the Dead celebration. According to historian Elsa Malvido, researcher for the Mexican INAH and founder of the institute’s death studies center, the allegory to death personified in the human skeleton does not have pre-Hispanic roots as Mexicans have been led to believe.

Instead, these current representations date back to medieval Europe, where Danse Macabre traditions used frivolous personifications of death as representations of the ephemeral nature of life. Malvido states that traditions such as skull-shaped sweets and bone-shaped bread already existed in Spain and southern Europe at that time.

How did these fearsome representations of death make their way into the traditional and spiritually elevated rituals in which Mexicans honored their deceased loved ones? According to historian Ricardo Pérez Montfort, the ideology of indigenismo — focused on the recognition of indigenous cultures and on questioning mechanisms of discrimination and ethnocentrism — was largely used by revolutionary officials during the Mexican Revolution to foster nationalism.

Viewing Hispanic culture as a manifestation of conservative political stances, they opposed all European-influenced traditions, especially those of spiritual character.

This is how the leftist government of Lázaro Cárdenas, motivated both by indigenismo and left-leaning anti-clericalism, officially isolated the Day of the Dead from the Catholic Church, encouraging a new Mexican nationalism through an “Aztec” identity.

With this, all Catholic elements of the celebration were replaced by an indigenous iconography centered on the veneration of death, which Cárdenas claimed was a revival of ancestral roots, and which historian Malvido has refuted as an adaptation of European traditions in an effort to extend political influence.

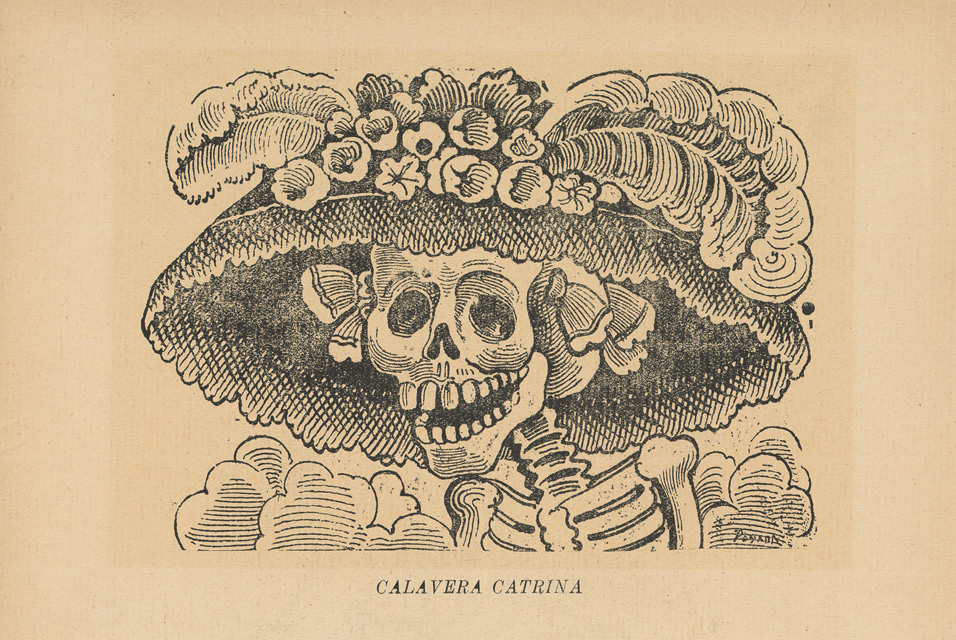

Mexican author Agustín Sánchez González, who has published articles in the INAH’s bi-monthly journal Arqueología Mexicana, claimed that although José Guadalupe Posada — creator of the iconic Calavera Catrina — is often portrayed as the “restorer” of Mexico’s pre-Hispanic tradition, there is little evidence that he was interested in Native American culture or history.

González explained that Posada was predominantly interested in drawing scary scenes influenced by European renaissance movements and the horrors painted by Francisco de Goya in the Spanish war of Independence against Napoleon. Thus, today’s Day of the Dead celebration may not be a revival of Mexico’s pre-Hispanic tradition, but a 20th century festivity that has been redeveloped.

The authentic celebration

According to historian Malvido, the pre-Cárdenas Day of the Dead was radically different from what is seen today, as it used to be a purely spiritual and mostly Catholic celebration.

She explained that on that day, it was customary for Mexicans to set up huge altars in the temples where the relics of the saints — considered man’s intermediaries before God — were exhibited: bones, skulls or other remains, the earth where they were buried or a part of the clothes they wore were part of the display.

The more the relics were visited, the more indulgences the faithful could gain. Thus, Mexicans used to tour their cities, going from church to church to venerate the relics of Saints and pay their respects.

At the conclusion of the short pilgrimage, parishioners would buy a loaf of bread or a sweet in the form of a relic, which was blessed by the priest, and finally placed on a table at home, along with the family saint and assorted fruits.

This tradition, according to Malvido, already existed in Europe and was adopted by Catholic believers in Mexico, where it maintained its religious significance until the indigenism of the 1930s branded it as a pre-Columbian tradition.

Returning to tradition

Day of the Dead has become a worldwide celebration, as people of Mexican origin have shared their colorful traditions outside the country. The appealing colors, music and joyful activities, as well as its representation in international films such as James Bond’s Spectre and Disney Pixar’s Coco, have further consolidated this celebration as part of the Mexican identity.

The festival plays a key social role in reaffirming one’s identity as part of a family and lineage of ancestors. When it comes to remembering and honoring the deceased, the celebration has successfully preserved its original purpose.

However, it is worth reconsidering what the essence of the celebration was before it was influenced by modern ideologies. The importance that the indigenous people attached to the destination of the soul points to a higher truth that is explicitly celebrated by Catholic belief: the fact that our soul is immortal and that we all have the opportunity to ascend to Heaven through spiritual efforts.