The Shang Dynasty (1556 – 1046 BC) was the first dynasty in traditional Chinese history to be supported by archeological findings. It replaced the Xia Dynasty, a semi-legendary regime, when its last king, Jie, was said to have become immoral, tyrannical, and lascivious. It was Cheng Tang who overthrew Jie, becoming the first king of the Shang Dynasty.

But as explained by Chinese wisdom, the virtue of the ruler determines the fate of the nation. And, not unlike the previous dynasty, the moral corruption of the last king of Shang, Di Xin (帝辛), spelled the end of the kingdom that had lasted 600 years.

Under the rule of Di Xin, the state was submerged in chaos. The king had given himself over to drinking and women, and neglected all affairs of the state. Accompanied by his wicked concubine Da Ji (妲己), the ruler committed all kinds of evil and cruel deeds. But his corruption did not last long.

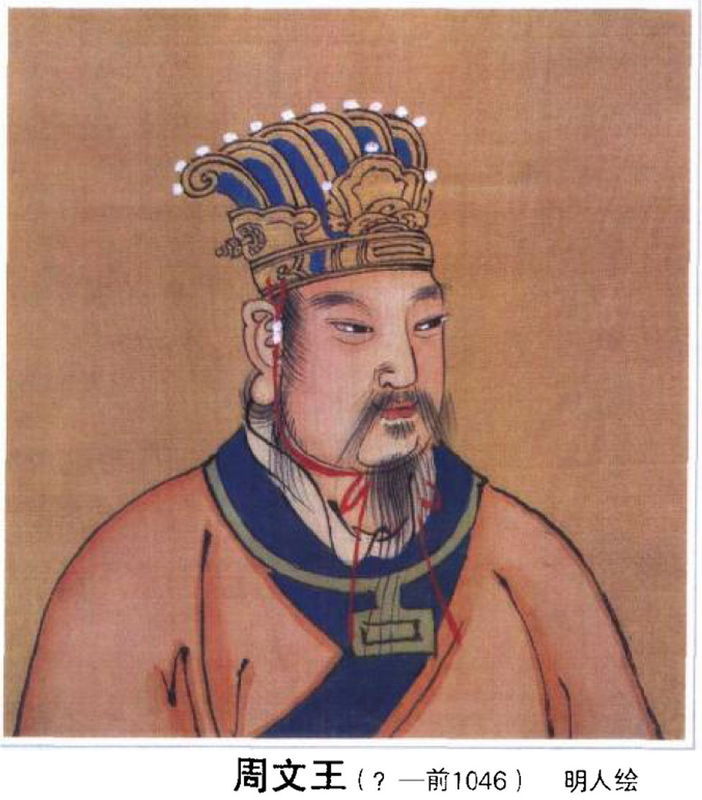

Amidst the decadence, the virtuous heart of Ji Chang (姬昌) shone forth. Starting as a kind-hearted count at the service of Di Xin, Ji Chang built up a small state — the Zhou (周) state — within the Shang nation, establishing nobility and kindness as the foundation.

Eventually, the small state increased in prosperity and power, until Chang’s son, Ji Fa, rebelled against the corrupt Di Xin, taking the throne and founding the Zhou Dynasty.

Influenced by his father’s righteousness, Wu established a kingdom that embraced and followed the Mandate of Heaven. All Zhou kings paid reverence to the divine and maintained upright and exemplary behavior in their private and public lives. This set high standards of moral conduct for Chinese rulers for generations to come.

Suffering tribulations due to the king’s jealousy

Ji Chang became the count of Zhou — a small state in present-day Shaanxi — at a very young age, when his father, Ji Jili, was betrayed and executed by Wen Ding, the then-Shang king, who was worried about Jili’s growing power.

It didn’t take long for young Ji Chang to become a good leader and gain the favor of his people. His righteous rule and upright conduct earned him so much popularity that the ruling Shang king, Di Xin, decided to imprison him.

In prison, Chang suffered many hardships, the most difficult of which was learning of the execution of his eldest son who had gone to plead for his freedom. Nevertheless, Ji Chang kept his composure and remained noble-hearted.

Chang was released after two of his loyal officials bribed King Di Xin with numerous gifts. The corrupt king was so satisfied that he not only released Chang, but also returned to him his personal weapons and granted him the special rank of Count of the West.

Before returning home, Chang seized the opportunity to request and achieve the abolition of the Burning Pillar punishment, a form of torture that the king and his concubine used to take as entertainment.

A fateful encounter

Under the unscrupulous rule of Di Xin, Ji Chang’s honorable governance in the Count of the West earned him great recognition among the nobles. Chang’s success at governing was in no small part due to his careful selection of officials. Following the advice of his father and grandfather, he was constantly looking for talented people.

His grandfather, the Grand Duke of Zhou, had told him that one day he would meet a great sage who would help him rule the state of Zhou. Fulfilling the prediction, Chang met an unusual man one day while hunting in the countryside. The old man was using an unbent nail as a fishing hook, which he said would catch only those fish that wanted to be caught. It was Jiang Ziya (姜子牙).

The meeting between Ji Chang and Jiang Ziya was recorded in the Six Secret Teachings, and described as a mythical encounter, common when two historical figures of ancient China met. After talking about politics and military strategy, Ji Chang decided to take the wise man to the court and appoint him prime minister.

Restoring peace and building a nation

As rebellions broke out across the nation against the king, the Zhou state steadily increased in power and prosperity under the rule of Chang and Jiang Ziya. In the following years, Chang led numerous campaigns in territories where the Shang king’s puppets were harassing the population and ruling corruptly.

With the dutiful help of Jiang Ziya, Chang annexed as much as two-thirds of the entire kingdom to his territory, but before he could see peace restored throughout the nation, he died of old age, bestowing the great mission upon his descendants.

It was Chang’s second son, King Wu (周武王), who would follow in his footsteps. Under the wise advice of Jian Ziya, Wu crashed the Shang in the Battle of Muye. Di Xi, who saw all his people revolting against him, set fire to his palace and died in it, while his wicked concubine, Da Ji, was captured and executed by Jiang Ziya himself.

Putting an end to numerous years of corrupt rule, King Wu and his successors founded the Zhou Dynasty, a new nation ruled by divine will. Its honor-based system of government emphasized virtue and rectitude among the people and led to the elevation of morals throughout society, consolidating the righteous values that would become the essence of traditional Chinese culture.

Although Wu was the one to conquer the Shang dynasty, he honored his father as the founder of the Zhou dynasty and posthumously titled him King.